Below is an excerpt from my book Pamela Tiffin: Hollywood to Rome, 1961-1974. In 1968 after abandoning her U.S. film career to make movies in Italy, Pamela returned to America after a 2 year absence. She garnered the female lead in the hit comedy Viva Max (1969) starring Peter Ustinov, Jonathan Winters, and John Astin. Below is a portion of the chapter “Back in the U.S.A.”

Below is an excerpt from my book Pamela Tiffin: Hollywood to Rome, 1961-1974. In 1968 after abandoning her U.S. film career to make movies in Italy, Pamela returned to America after a 2 year absence. She garnered the female lead in the hit comedy Viva Max (1969) starring Peter Ustinov, Jonathan Winters, and John Astin. Below is a portion of the chapter “Back in the U.S.A.”

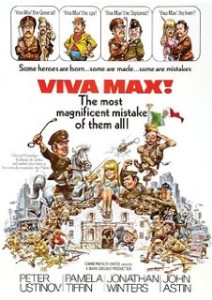

Pamela Tiffin was back in the United States in 1969 starring opposite Peter Ustinov in the political satire Viva Max. It was her lone American movie since relocating to Italy. In the film version of newspaperman Jim Lehrer’s 1966 comic novel a modern Mexican general who, with a ragtag bunch of soldiers from Nuevo Laredo, retakes the Alamo causing U.S. embarrassment while trying to avoid an international incident. The book was a bestseller despite some less than stellar reviews such as in the New York Times where critic Martin Levin said it “begins with the impossible and descends to anticlimactic foolishness.”

Jim Lehrer sold the rights to the book for about $45,000. It was to come from the amount of money the producer would raise for the film’s entire production budget rather than from Hollywood’s elusive “net profits.” Reportedly, Lehrer used the money to quit his newspaper job and head to Washington, DC to try to land a TV anchor gig. He undoubtedly succeeded with public television’s The MacNeil/Lehrer News Hour, which morphed into The News Hour with Jim Lehrer and then the PBS News Hour.

In September 1967, it was announced that Viva Max was to begin filming the following month in San Antonio, Texas. Mark Carliner Productions was producing for MGM. Thirty-year-old Carliner was a former CBS television executive and this was his first motion picture project since leaving the network. Arthur Hiller was attached to direct. An experienced comedy director, his recent credits up to that point included The Wheeler Dealers; The Americanization of Emily; Penelope; and The Tiger Makes Out. The novel was adapted by novelist-turned-screenwriter Elliott Baker whose prior credits included A Fine Madness and Luv.

For unknown reasons, the movie was postponed. Almost a year later, Mark Carliner announced that the movie was now set to commence. However, it was now a Commonwealth United production in association with CBS. Under a new plan of providing new movies to be shown on television, the TV network put up an estimated $800,000 towards the $2.7 million budget with a guaranteed broadcast release in January 1973. Exteriors would be filmed on location at the Alamo and interiors would be filmed at Cinecetta Studios in Rome.

Producer Carliner lost his director, Arthur Hiller when the project moved from MGM to Commonwealth United. He was replaced by Emmy-winning TV comedy director Jerry Paris. He worked on such hit TV series as The Joey Bishop Show; The Dick Van Dyke Show; The Farmer’s Daughter; The Munsters; Here’s Lucy and had in release two 1968 movie comedies, Don’t Raise the Bridge, Lower the River with Jerry Lewis and How Sweet It Is! with Debbie Reynolds.

Peter Ustinov would be starring as the Mexican general with filming to begin in the spring of 1969. The actor accepted the part because he liked the premise that though the U.S. is technologically equipped enough to track the flight of birds, they could not detect a small group of men crossing the border to take over the Alamo with indirect help from the local police. Jim Lehrer was happy with the casting of Ustinov as well and remarked when told who was cast, “When they showed me a picture of Ustinov in his uniform on a great white horse, I nearly dropped. He WAS Max!”[i]

Speculation was running rampant on who would play the lone major female role that of the pretty blonde gift shop cashier who is also a radical college student taken hostage along with two others. The top contender was Amy Thomson, an actress being hailed as the “New Garbo.”[ii] Well, at least her managers were calling her that. She had just made an impressive film debut in the Richard Widmark western Death of a Gunfighter. Alas, she did not get the role and the producer somehow decided on Pamela Tiffin.

Commenting on her character, Pamela said, “It’s a marvelously funny role. I play this girl who could have been yesterday’s cheerleader or baton twirler, but today she is a go-go political science major, an activist who loves to use big words like ‘absolutism’ or ‘totalitarian.’ She might never have been out of San Antonio yet you know that she cares for the world.”[iii]

To keep the comedy quotient high, Jerry Paris surrounded Ustinov with a number of talented comedic actors including Jonathan Winters, John Astin, Keenan Wynn, Harry Morgan, Kenneth Mars, and Gino Conforti. Among the young actors chosen to play Mexican soldiers was tall and lanky Larry Hankin. He did comedy improv and began working in Hollywood in 1966 with a guest spot on the TV sitcom That Girl. He worked twice prior with Paris on the unsold TV pilot Sheriff Who and the comedy film How Sweet It Is!

To keep the comedy quotient high, Jerry Paris surrounded Ustinov with a number of talented comedic actors including Jonathan Winters, John Astin, Keenan Wynn, Harry Morgan, Kenneth Mars, and Gino Conforti. Among the young actors chosen to play Mexican soldiers was tall and lanky Larry Hankin. He did comedy improv and began working in Hollywood in 1966 with a guest spot on the TV sitcom That Girl. He worked twice prior with Paris on the unsold TV pilot Sheriff Who and the comedy film How Sweet It Is!

Peter Gonzales Falcon was also cast as a soldier. A senior majoring in Drama/Speech at Southwest Texas State College, he accompanied a female friend to an open casting call for the movie. While waiting in an outer room, he heard someone yell, “That face!” That someone was Jerry Paris and it was Mexican-American Gonzales Falcon’s handsome features and bone structure that got Paris excited. After reading for the director, Peter got the role. Knowing it was going to be at least a twelve week shoot including time in Italy, the excited young man decided to drop out of school to pursue his dream of acting. When asked if he was familiar with the movie’s leading lady, Pamela Tiffin,” Gonzales exclaimed, ““Oh yeah! Pamela was a big movie star. I first saw her in State Fair and then in another film. I thought she was just wonderful and very beautiful.”[iv]

Another young actor cast in the role of a government representative was handsome sandy-blonde haired Eldon Quick who started his acting career at the American Shakespeare Festival in Stratford, Connecticut. He had a number of TV sitcom appearances under his belt including Occasional Wife; Gomer Pyle, U.S.M.C.; The Monkees; and Bewitched and was adept at comedy usually cast as the nerdy brain. Viva Max was his second movie after a supporting role in the Academy Award-winning In the Heat of the Night.

Location shooting began in the spring of 1969, but a battle quickly erupted between the film’s producers and the Daughters of the Republic of Texas who were the gate keepers to the Alamo holding custody to it and the grounds within its walls. The organization originally gave permission to shoot inside and outside the Alamo. A few scenes, including the guided tour of the Alamo, were shot within, but the Daughters withdrew their support when they realized Viva Max was going to be a satire. They did not want the movie to be filmed anywhere near their sacred mission where James Bowie, Davy Crockett, and 185 soldiers battled General Santa Anna and his army in 1836. They found the movie to be blasphemous especially the part where the Mexican flag is hoisted over the Alamo.

The producers then found out that the Daughters had no jurisdiction over the plaza outside the Alamo, which was city-owned property. They went to the San Antonio City Council to issue a permit. However, the Daughters were not giving up. The City Council had to make a decision and heard two hour testimonies from both sides.

The DRT president was a woman named Mrs. William Lawrence Scarborough who told the council, “I come before you to plead with you and ask you not to permit this movie on the premises owned by you. We feel this movie is a mockery and a desecration of our heroes who died for our liberty there.”[v] A representative of the movie countered and declared, “There is nothing in this movie that could possible be offensive.”[vi]

The war of words continued in the press. Mrs. Scarborough bemoaned to anyone who would listen, “This is not a movie we could be proud of. Why couldn’t they make a beautiful movie like John Wayne did?”[vii] Producer Mark Carliner issued a statement and said, “The movie does not desecrate, defame, deface, damage or compromise either the structure or heritage of the Alamo.”[viii]

The city council declared it a draw. By a vote of six to two, it gave permission to shoot on city held property leading up to the doors of the mission. However, there was to be no filming inside or on the grounds of the Alamo nor could they touch the outside walls. The people of San Antonio were not against the movie being filmed in their city and actually signed up to play extras. Eighty-seven Mexican men were cast as soldiers in Max’s army and about forty Caucasians were cast as members of the city’s right-wing militia. A native Texan, Peter Gonzales added, “The whole movie was a big deal to San Antonio. It was a big city, but was becoming a player with other big cities at the time. The long awaited Hemisfair [the 1968 World’s Fair] was in full gear. Everyone was an extra even the city’s richest people who were there in the heat all day. Millionaire fathers would introduce their beauty queen daughters to Jerry Paris hoping to get them in the movie.”[ix]

Despite the ruling and the welcome mat the people of San Antonio put out for the movie people, the Daughters of the Republic were still not done fighting just like their outnumbered Alamo comrades. The movie’s attorney reported to the Council that the ladies were disrupting filming on city property. They stood in front of the Alamo in black costumes and draped the shrine in black paper. The latter action was in protest due to the raising of the Mexican flag over the Alamo. He challenged that the Daughters were miffed by the decision and were doing this for personal vengeance. Mrs. Scarborough pooh-pooh the attorney’s accusation and remarked, “I can’t think of anything lower than the idea of making a comedy about a shrine where heroes died. It’s like making a comedy on the fallen heroes of Vietnam.”[x]

Scarborough then filed a petition for a restraining order against the movie makers claiming harassment and threatening actions. The court action also stated that already completed filming and more scheduled “will do irreparable damage and harm to the Alamo and to the continued efforts of its custodians to make it a symbol of Texas independence and freedom.”[xi] The filmmakers countered that they were the ones being harassed by Mrs. Scarborough and her organization.

While his producer battled the meddling Daughters of the Revolution, director Jerry Paris kept plodding on. Eldon Quick, however, was not impressed with his directing style though. “We gathered in the city of San Antonio perhaps the greatest collection of comedic talent assembled since It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World,” he commented:

Unfortunately we didn’t have Stanly Kramer to direct us. We had Jerry Paris. It’s hard to imagine a more typical Hollywood-type director—since we were in Texas one could say he was all belt-buckle and no cattle. As I watched the filming, I saw scene after scene fizzle away.

A typical scene preparation went this way—Jerry would urge the actors in the scene to go for the real human values. His approach seemed to be very ‘Method.’ The actors would read through the scene being very legitimate. Jerry would then ask them to do it again—again a very legitimate rehearsal. Jerry would ask for another go through, but by now the talent of the caliber we were working with are bored out of their minds and someone would do something wild or nutty just to relieve the boredom. Then Jerry would say, ‘Oh, that’s good, keep that.’ The other actors would say to themselves, ‘If that’s in the scene no one in the audience will even know I am in it.’ So next rehearsal some comedic take by someone would be added, and Jerry would say, ‘Oh, that’s good keep that in.’ Scene after scene faded away into shtick acting.

A typical scene preparation went this way—Jerry would urge the actors in the scene to go for the real human values. His approach seemed to be very ‘Method.’ The actors would read through the scene being very legitimate. Jerry would then ask them to do it again—again a very legitimate rehearsal. Jerry would ask for another go through, but by now the talent of the caliber we were working with are bored out of their minds and someone would do something wild or nutty just to relieve the boredom. Then Jerry would say, ‘Oh, that’s good, keep that.’ The other actors would say to themselves, ‘If that’s in the scene no one in the audience will even know I am in it.’ So next rehearsal some comedic take by someone would be added, and Jerry would say, ‘Oh, that’s good keep that in.’ Scene after scene faded away into shtick acting.

This may have effected Jonathan Winters most of all. His ad-libs and improvisations were truly hilarious. The cast and crew would fall down laughing in rehearsals. When the camera was rolling, Jonathan would try to repeat what he had done in rehearsal and because it was no longer spontaneous it just fell flat. Jerry should have filmed the rehearsals and let the camera run empty for the take. If only the humor that was in the script had made it to the screen.[xii]

Larry Hankin agrees with Quick’s opinion of Paris. “Though Jerry liked my acting a lot, we had a very huge ‘disagreement’ while we were shooting in front of The Alamo one day in front of the entire cast (including 50 extras) and again at a screening at Cinecitta in Italy (where we did some interiors of the Alamo which they replicated perfectly)” he wrote:

In general, he was a perfect, ‘smile, you’re on camera’ TV director, but not a good film director is the best I can say. He had no idea how to work with actors—particularly talented ones, which he had in Viva Max. All Jerry wanted was to be liked—toxically so. He wasn’t a storyteller. He was an excellent traffic manager, which is perfect for sitcom directing and he was obviously great at that.[xiii]

Writer Michael Etchison was on location the day when director Jerry Paris was shooting the scene where Ustinov’s Max takes Pamela Tiffin’s character to a gardener’s shed to seduce her, but it turns into a political conversation. It was shot on what was the Japanese pavilion at the 1968 HemisFair. He reported that Tiffin spent most of the day in her hotel room rehearsing as well as preparing for the role with paying special attention to her costume (white blouse and miniskirt) and makeup. Pamela commented to him, “It has to be right. The way you look changes the character you play.”[xiv] To prove her point, she recited some of her dialog while pretending to chew gum.

Describing the actual shooting of the scene, Etchison reported, “Ustinov does not need to imagine nervous sweat; he stalks and paces, circling Miss Tiffin like a dog preparing to lie down. No one can forget he is Ustinov, but no one could be unmoved by his awkward explanation of his plan.”[xv]

Though Pamela Tiffin mingled with Peter Ustinov and Jonathan Winters, she and the other bigger stars did not hang out with the actors playing soldiers or other small roles. Peter Gonzales explained, “There were tiers of actors on this shoot, but that is a Hollywood thing. This was my first film so I was not acquainted on how things worked on a shoot. The main stars hung out separately from the featured players who stuck together. It was very clannish—sort of like a pyramid.”[xvi]

All three actors had minimal contact off-camera with Pamela Tiffin. Despite his improvisation talents, Larry Hankin admitted to being quiet and shy. Suffice it to say, he did not make much contact with Pamela on the set and never off it, but found her to be “cool and pretty.”[xvii] Gonzales said, “I only interacted with Pamela a little bit on the shoot. When I did, she was always very nice. She seemed to get along beautifully with everyone.”[xviii] Eldon Quick also had very little contact with the actress. “As I was a bit player in the movie, I was not in her social circle,” he remarked:

I don’t remember her socializing much with the cast, we were almost all male and our sense of humor was really pretty crude. It was rumored that she and Peter Ustinov were sharing dinners in his hotel room and perhaps Peter was the only cast member she was friendly other than cordial with.

I do have two memories of Pamela—one was of her table manners. They were impeccable. It was obvious she had spent considerable dinning among the élite of Europe. For instance, Americans will butter a slice of bread then take a bite out of it. Pamela would break off a small piece of bread, butter it, and then most daintily put it in her mouth. She reeked of ‘class.’

My other memory is that during filming outside of the Alamo, cast members who were waiting for their scene or, like me who wanted to watch the filming, would sit on the grass in front. Pamela wandered onto the lawn in her horseback riding clothes carrying her purse and a bag with a riding crop in it. She placed the bag on the lawn then turned to spread out a blanket to sit on. As she bent over to spread out the blanket, she goosed herself with the riding crop. She sprang up, spun around, and cocked her arm to deliver a killing slap to who ever had assaulted her. As I was the nearest one, she glared at me ready to let me have it. I blinked at her trying to look innocent, and trying not to laugh, pointed at the riding crop. She relaxed, but never spoke to me again.[xix]

With shootings delays occurring frequently due to the court order challenges, it stretched out the time spent in Texas to the chagrin of a cadre of Italian crew members who despised the Texas cuisine. Co-star John Astin noticed they were only eating cold meats and cheese in their room and invited ten of them out to dinner. He took them to a grand restaurant called La Louisianne where they enjoyed a wonderful meal with a huge tab to match. The liquor bill alone was $190. Afterwards, Astin quipped to writer Bob Rose, “The next time I see an Italian eating alone in his room I am going to ask him for a bite.”[xx]

[i] Michael Etchison, “Remember the Alamo? It’s Being Retaken,” Los Angeles Herald-Examiner, Apr. 6, 1969, E-1.

[ii] Norma Lee Browning, “Hollywood Today: Is ‘Coco’ for Kate?” Chicago Tribune, June 23, 1969.

[iii] Marika Aba, “Pamela Tiffin—American Sex Queen in Exile,” Los Angeles Times, July 6, 1969.

[iv] Peter Gonzales-Falcon, Telephone interview with author, Aug. 19, 2014.

[v] UPI, “’Viva Max!’ Wins Alamo Film Battle,” Los Angeles Times, Mar. 29, 1969.

[vi] Ibid.

[vii] UPI, “Alamo ’69 Pits ‘Max’ Against Texas Ladies,” Newsday, Apr. 2, 1969.

[viii] Ibid.

[ix] Gonzales-Falcon, Telephone interview with author.

[x] UPI, “Alamo ’69 Pits ‘Max’ Against Texas Ladies.”

[xi] UPI, “Texans Up in Arms Over Alamo Movie,” Los Angeles Times, Apr. 11, 1969.

[xii] Eldon Quick, Email interview with author, Sept. 13, 2013.

[xiii] Larry Hankin, Email interview with author, Sept. 18, 2013.

[xiv] Etchison, “Remember the Alamo? It’s Being Retaken,” E-10.

[xv] Ibid.

[xvi] Gonzales-Falcon, Telephone interview with author.

[xvii] Hankin, Email interview with author.

[xviii] Gonzales-Falcon, Telephone interview with author.

[xix] Quick, Email interview with author.

[xx] Bob Rose, “Food for Thought—after ‘Candy,’” Boston Globe, Aug. 31, 1969.

I vaguely recall when VIVA MAX opened, but had no idea that Pamela was in it. It looked like a bomb to me, so I have never actually viewed it. It still doesn’t sound very good to me, but Pamela looks great in those photos.

Actually a very amusing film. Pamela is as usual gorgeous in this and quite comical.